For communication we are using alphabets, language, symbols, gestures, words, utterances, intonation and even highly sublime effects ("I felt a certain weakness in his appearance"). All of them are – according to the interpretative paradigm – representations, in the sense of systems of meaning, and have been acquired in social sitautions, a process that sociology describes as socialization. These representations, however, are not objective, divine facts, but are interpreted every time by all interacting partners. The criterion for successful interaction is therefore a reciprocal, approximatively identical interpretation by all partners of the interactive process. Only then are the meanings of representations shared and the interaction can benefit from mediated or face-to-face communication (Luckmann 1984).

Since virtual media and communication technologies have been starting to transform our society, we witness the evolution of new forms of social interaction patterns and a shift from place to space. Virtuality, then, is simply a technological mode of opening new social spaces and the very moment we will realize how distant the dream of a colonization and exploration of our galaxy remains, these virtual worlds might become an almost infinite source of new social spaces, which we can shape and explore according to our needs and wishes. But already today new social phenomenons arise, such as virtual communities where »membership can replace a sense of belonging to a place with a sense of belonging to a community« (Handy 1995).

The concept of common interpretative spaces shall add a certain social dimension to the discussion of virtual modes of interaction and I have used the popular metaphor of »space« for that purpose, a metaphor that is currently also used in related approaches (Nonaka/Konno 1998, Boisot 1995). The model presented in this paper is thus an attempt to build new analytical frameworks based on traditional, approved theories and concepts, which allow us to analyse these new social phenomenons.

Common interpretative Spaces

For the study of social phenomena we need practical concepts of how interaction between individuals takes place. In the following a basic model is presented, which is built within the interpretative paradigm around the core idea of "common interpretative spaces" (CIS) and draws heavily on theories of Alfred Schütz, Edmund Husserl, Peter L. Berger, Thomas Luckmann, Erwing Goffman and Stuart Hall. Although I concentrate on the discourse around virtual communities and virtual modes of organizing, the presented model can easily be applied to other social phenomena as well. Namely in the field of knowledge management, where information processing and sharing of knowledge are dependent on a well-established CIS, such a transfer is indicated (Diemers 1999).

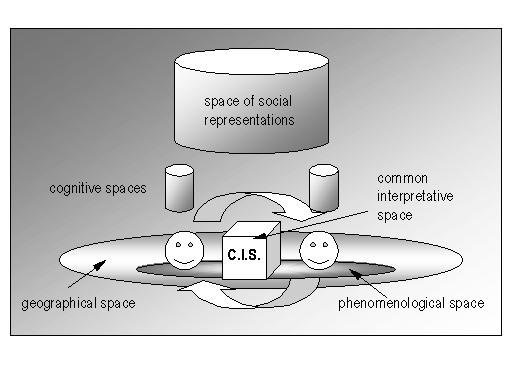

Figure 1: A spatial model of face-to-face communication between two individuals

In figure 1 a basic model of face-to-face communication between two individuals is visualized. Geometrical shapes are representing different spaces, namely geographic space, phenomenological space, common interpretative space, cognitive space and space of social representations. In the following these different spaces will be outlined in brief and a special focus will be made on the common interpretative space.

The foundation for all social interaction is geographic space, which covers our whole »world-in-reach«. Alfred Schütz and Thomas Luckmann distinguish between a world within actual reach and a world within potential reach. The world within potential reach is furthermore differentiated into restorable reach, locations I’ve been to in earlier times, and attainable reach, places of which I have knowledge about and which I could reach if I wanted to. The concept of geographic space comprises both my worlds within actual and potential reach and is the unquestioned, spatial arrangement of my daily life-world (Schütz/Luckmann 1974; 1983).

Phenomenological space is a part of geographic space and corresponds to Schütz‘ conception of »world within actual reach«. Phenomenological space is the immediate world »in sight« that arranges itself spatially and temporally around the individual as its center. External objects in phenomenological space appear to us as phenomena, either through actual perception, attentive advertence or subsidiary awareness, and those perceived phenomena are structured and identified according to our individual set of typifications and meaning-structures, which reside in our cognitive space. Without this unnoticed dialectic between phenomenological space and cognitive space the world around us would appear as a blurred, unstructured sensory stimulation devoid any meaning or sense. Thus, we are permanently constructing a meaningful picture of the phenomenological space around us, which in the end constitutes the »paramount reality« of our perceived, unquestioned daily life-world (James 1890, Schütz/Luckman 1974).

The cognitive space is constituted by the individual stock of knowledge, the system of relevance and the conceptual map, which links together the different typifications of our language. When we perceive objectivations, we are matching them with our conceptual map in order to attribute the appropriate typifications. Meaning, thus, is never in the perceived object itself, but cognitively constructed by the perceiving subject (Hall 1997). Schütz describes the acquisition of knowledge as a sedimentation of current experiences in meaning-structures according to relevance and typicality. All experiences and all acts, then, are grounded on relevance structures, which determine »what really matters to us« (Schütz 1974). These three elements – a biographically sedimented stock of knowledge, relevance structures and the conceptual map of our typifications – combined form our cognitive space, which is by definition individually unique and determines the way we construct the world around us.

The space of social representations comprises the social system of representation and makes it possible that two individuals, who have never met each other before, are nevertheless able to interact in a social setting and attribute meaning to the utterance of the other. Hall actually distinguishes, to be precise, two systems of representation: the first system is a conceptual map of socially relevant objectivations and their relationship to each other. Within such a map concepts are organized, clustered, arranged and classified in complex relations, for example by using the principle of similarity or difference. The second system of representation consists of culturally specific signs – language, symbols, pictures, body-language...etc. – that allow us to articulate and share our conceptual maps (Hall 1997). The space of social representations is created through the process of institutionalization, when social practices are habitualized, shared and legitimated within a community. It is then the process of primary and secondary socialization which makes us internalize objectivations – a combination of signs and conceptual maps – into our individual cognitive space (Berger/Luckmann 1966). At this point now, following the interactional model, our two individuals each have a cognitive space, which was derived from the social space of representations and is constantly being compared and updated with it, share a geographic space and currently have their phenomenological spaces in congruency.

Finally, the common interpretative space is the specific set of signs, shared meanings, norms and values of two or more individuals interacting face-to-face, in »co-presence« with each other. It will be created initially based on individual cognitive spaces, but undergoes a transformation during the process of »focused interaction«. Assuming that both individuals have a similar cultural background, i.e. their cognitive space has been formed within the same social space of representations, they will use roughly the same code of signs to express themselves or, using Goffman’s terminology, to play their roles. If also their meaning-structures do correspond, i.e. they are both attributing the same meanings to used signs, the interaction will proceed without problems, until a »situational inadequacy« occurs and a role is performed other than expected. At this point there are very probably differences in norms and values relevant to the interactional modality and these differences have to be resolved by modifying the common interpretative space accordingly (Goffman 1959; 1969). Assuming that a specific interaction is carried out repeatedly, the social situation will turn out to be less and less problematic for our two individuals. The process of institutionalization makes interaction easier by improving the CIS and maybe our two individuals are learning more about each other in the course of time, in that they share knowledge about their system of relevance, their typifications, their values and norms in other areas and former experiences, which sedimented in their cognitive space. The historical line of their interaction will also become part of the CIS and at a certain point socioemotional contents – emotions, trust, friendship, tradition, bonds, ...etc. – may become part of the common interpretative space. Within such developed CIS new signs, meaning-structures, values and norms may evolve over time, which are then shared only by the interactional partners of the CIS and constitute »finite provinces of meaning« (Schütz/Luckmann 1974).

The Case of virtual organizations and Communities

Having introduced the core concept of CIS within a basic model for social interaction, let us widen our analysis from the diadic, two-person case towards more complex cases of interaction within organization and communities. In the title of this section a certain difference between organizations and communities is postulated, and these differences will be elaborated below, even if we have to be aware of the fact that these two concepts have a lot in common and overlapping, semantical areas.

Within the scope of this article the term organization is used from a sociological perspective as »socially constructed forms of cooperation«, which are built actively in order to achieve a specific set of goals. Every organization is built on certain norms and values and has a distinct structure, which coordinates and redirects the activities of organizational members and available resources towards lasting organizational functionality, in the sense that its goals are permanently attained (see March/Simon 1958, Pugh/Hickson 1976). To put it more simply, we can say that spontaneous modes of organization evolve, whenever one person alone is not able to solve a specific problem, and that such social forms of cooperation – assuming that they have proven to be adequate ‚problem-solvers‘ – can become institutionalized through repeated social practice. Berger and Luckmann identify the process of increased institutionalization and highly differentiated and specialized organizations as a main feature of modern societies (Berger/Luckmann 1966). Newer social theories on organizations are stressing the fact that an organization‘s existence is constantly in danger, as there is a limited interdependence between the members of the organization, limited rationality – and thus predictability – of the organizational members‘ behaviour and a limited legitimation of the goals of the organization (Friedberg 1992). This aspect of both formal and informal dimensions of organizational structures has received increasing popularity in the last decades (Morgan 1986), and this shift from a functional, instrumental view to the manifold, pluralistic facets of organizations and its culture brought current approaches in closer contact with theories and research on communities and revealed the importance of social interaction and commonly established interpretative spaces for the study and discussion of organizations.

In the last years this development has taken a second, even more dramatic turn: the coming of a new type of organization (Drucker 1988). New media and communication technologies have led to a significant change of the way we interact and the way we work together, therefore it is essential not to constrain this phenomenon to its technical side, but to consider virtualization as a major social process (Diemers 1997; 1998a). Thus, virtualization has a significant impact on social interaction and relationships within organizational boundaries in a business context (Brosziewski 1998), and we can increasingly observe the reconceptualization and modification of organizational roles and norms (Cash 1991). These developments have finally led to new forms of organization, which have been ascribed accordingly to the term of virtual organizations (Nohria/Berkley 1994, Davidow/Malone 1992). The main feature of these new, virtual modes of organizing is the fact that mediated, virtual forms of communication and interaction – for example groupware, electronic mail, videoconferences, internet applications...etc. – play a central role within the organization and substitute direct, face-to-face communication to a large extent, while its structure reflects this constitutive quality of organizational relationships and resembles to a virtual, heterarchical network. These structural differences are important, when it comes to discern virtual organizations from virtualized organizations, the latter of which comprises traditional organizations, which use new media and communication technology as a means to an end, but nevertheless retain strict hierarchies, geographically confined spaces and a significant amount of face-to-face contact among its organizational members (Diemers 1998b).

We now have to ask the main question of what role and importance do common interpretative spaces have for virtual organizations. According to our conception of common interpretative spaces, communication in virtual organizations can basically take two idealtypical forms, either the form of indirect, mediated communication, or the mode of direct, face-to-face communication, which Schütz described as the »immediate experience of the other in my everyday life-world« (Schütz 1974). As introduced in the basic interactional model above, the CIS is usually established in such face-to-face situations. If, however, we assume that mediated forms of communication prevail within organizational networks of relationships, the basic question is, whether common interpretative spaces can fold up with the same quality and richness, or whether specific, CIS-related problems may arise in virtual organizations. According to Weick one very important function of organizational communication is the making of sense in organizations, an issue that is increasingly important in virtual modes of organizing. Members have to be permanently supplied with emotionally rich components – such as values, norms, visions and legitimations – from their organization and have to be constantly reassured that they are "doing the right thing" and that their choice of membership was right (Weick 1996). The organizational goals have to be ranked above individual goals, which are often standing in conflict with them. We should finally consider the fact that emotional bonds, friendships or social networks – an organizational phenomenon that is best described with the German "Seilschaften", i.e. the metaphor of mountaineering roped parties, who help and depend on each other while walking to the top – are keeping organizations alive and functional. How can these emotional bonds and networks evolve in virtual organizations? In this context a well-established CIS has the primary role of assuring the survival and efficiency of virtual organizations. Charles Handy identifies accordingly trust, a sense of mutuality and reciprocal loyalty as inevitable requirements for virtual organizations. Given the potentially harmful consequences of poorly working CIS, he proposes the »concept of community membership«, which abandons the traditional notion of organizations as means to an end, where members work in exchange for some sort of payment, and calls for a transformation of organizational structures into communities, where individual efforts and commitment are rewarded with a sense of belonging, mutual trust and identity (Handy 1995). Given this interesting turn, which is induced by new media and communication technologies, the two concepts of organization and community are no longer opposed to each other and may enter combined discourses.

Thus, let us focus now on virtual communities and widen the spectrum of our analysis. The sociological notion of community usually opens large patterns of diffuse associations, which might include social networks, security, social order, family, neighbourhood, clans, emotional bonds, identity and several more. This wide semantic scope combined with a certain historical and normative burden, which dates back to early sociological uses of the concept of community, for example by Tönnies, who opposed the idealistic model of community to a rather pessimistic picture of modern society (Tönnies 1963). With the increasing virtualization of society, however, the term of community has received new popularity, but most authors are not dwelling too much on the different associations and interpretative patterns, which go along the use of community as an open label for different kinds of social phenomenons. One exception here is Komito, who delivers a distinct analysis of the different facets of communities in the context of virtual modes of social interaction. The basic distinction is made between »proximate communities«, where a CIS is constructed on the grounds of physical proximity and involuntary membership, »moral communities«, where a shared CIS is based on moral bonds, communal solidarity and a sense of common purpose and commitment, and »normative communities«, such as communities of practice or communities of interest, which are not restricted to geographical places and share common values and norms (Komito 1998). An interesting point is the fact that all three types of community can be found in virtual communities, which sometimes started as normative communities, later developed into moral communities and even social phenomenons of proximate communities appeared. Rheingold uses in this context the expression of »grassroots groupminds« to describe virtual communities, which grew steadily around many virtual fireplaces in the form of Usenet discussion groups or bulletin board systems, where likely-minded people came together and evolved into moral communities with high levels of mutual support and solidarity (Rheingold 1995). Mosco, on the contrary, rates the discourse of caring, virtual communities as a myth, which is used as a legitimizing argument within the current discourse around cyberspace and virtual worlds. With a glance at a long sociological tradition of community research he reminds us that communities are not just about romantic neighbourhoods and caring for each other, but also about strong social conventions and processes of exclusion and inclusion, which can eventually lead to social minorities and stigmatization (Mosco 1998).

The most important point, however, within the scope of this article is the fact that virtual networks can be media platforms, where common interpretative spaces of social networks constitute social spaces (Harasim 1993). A virtual community, thus, establishes a CIS through mediated forms of communication and current research on virtual communities – some of which will be presented in the next chapter – supports the view that these communities show very similar patterns of interaction and share many qualities of non-virtual communities. Some virtual communities do arrange face-to-face meetings of its members, but there are many other examples of communities where such »real-world grounding« has never taken place. If these ungrounded virtual communities – and here we are rejoining our argumentation line of virtual organizations – succeed in establishing a CIS of such a quality that typical community functions are satisfactorily performed, this result would be applicable to virtual organizations, which could then be set up within a community-oriented framework.

Empirical argumentation

So far we have outlined a basic model of social interaction, both in a virtual and non-virtual setting, and the concept of common interpretative spaces has been discussed in the context of virtual organizations and communities. The discussion until now boils down to the main question of what role does face time play in virtual modes of organization and community, or, to put the question a bit differently, is it possible to establish a functional CIS for successful interaction solely on virtual media platforms? At the current state of research – and, not to forget, degree of social virtualization – this main question can’t be answered with a simple yes or no. But we can lay different strands of research on the scales in order to gain a better argumentative stance in the ongoing discussion. Furthermore, we can then investigate differences between the establishment, functionality and upholding of CIS in virtual and non-virtual environments. For that purpose we can look at both virtual communities and virtual modes of working in business contexts, which range from virtual technologies as a supporting tool in daily work to complex forms of virtual organizations and telecommuting, where new media and communication technologies play a constitutive role.

After a first glance at different publications of empirical research, it becomes obvious that there are currently two opposing discourses, which are – unfortunately – often used as a scheme of conclusive argumentation. One discourse is about the opportunities and benefits of virtual modes of working and community building, where manifold stories are told about, for example, increased productivity, higher flexibility, competitive advantage, taking the challenge of globalization, or – within the discourse around virtual communities – examples of high levels of solidarity, new forms of friendship, love, self-esteem and identity. This discourse could be called a general »cyberphil« discourse and within those research findings the issue of poorly established CIS is seldom raised. The other discourse – let us call it accordingly the »cyberphobic« discourse – is about problems, conflicts and unresolved issues within virtual modes of socializing and cooperation. Here we find a heterogeneous discourse, which is focusing more on deficits of virtual media and communication technologies and could be imputed to the argument that virtual forms of interaction are inferior to face-to-face communication and the CIS is poorly established. Which discourse is now right? I think – and here I’m drawing on the »multiple perspectives« approach of relational constructivism (Morgan 1983; 1990, Dachler 1997) – it is the question, which is wrong. Both discourses are focusing on the same basic issues and in order to get a more appropriate picture we have to consider both approaches to be right and take advantage from findings of both discourses.

Interesting areas of research are virtual business environments and empirical studies on possible social conflicts and problems, which may arise therein. Studies on the use of electronic mail in business environments have a quite longstanding tradition and a consent exists to the extent that computer mediated, asynchronous communication suffers from the limitational character of e-mail messages. Due to a lack of transmitted context information, the emotional content of messages is often misinterpreted or wrong priorities and relevancies are attributed, which in the end are leading to misunderstandings as a constant, organizational source of conflict (Stegbauer 1995; 1996, Markus et al. 1992). These findings support the view from earlier social-psychological research on computer-mediated communication, which emphasizes its inferiority to face-to-face communication due to fewer channels, less context and many resulting misunderstandings, which makes the building of trustful relationships and communities with a sound common interpretative space difficult (Kiesler et al. 1984). The same issue is tackled by a recent empirical study from the University of Texas on trust in virtual teams, which revealed that the conventional patterns of trust evolution in face-to-face interactions cannot be applied to virtual modes of organizing. Instead of trust to evolve slowly and gradually over stages through repeated interaction and institutionalization of relationships, trust in virtual teams tends to be established – or not – right at the outset, which gives the first, initial contact of virtual team members a crucial role (Coutu 1998). Other, related forms of mediated interaction are virtual conferences, which have already gained a certain popularity in the academic world. Brill and de Vries analyze retrospectively their own virtual conference on "virtual economies" and come to the conclusion that in spite of certain problems, which originated mainly in technical problems and a certain "lack of routine" of conference participants and organizers, the result was in the whole very promising and no serious deficits in terms of common interpretative spaces could be attested (Brill/de Vries 1997; 1998). An equally positive image is presented by studies on virtual organizations in general (Charam 1991), or – as a good example of the large benefits generated by virtual modes of organizing – studies on networks of learning in the field of biotechnology (Powell et al 1996).

Werner Voss conducted a quantitative empirical study on telework and enriched his results with various other empirical research results in the field of virtualized modes of working together in a business environment. His findings give a generally positive picture and all serious problems of telecommuting are related to poorly established CIS or general problems in the social dimension (Voss 1998). From his research, however, it becomes also clear that the field of study of teleworking is a rather immature one, where the general research agenda has to be enlarged both in scale and scope (see for a proposal Handy/Mokhtarian 1996). At the same time an increased focus should be made on social aspects and implications of telecommuting models, touching questions such as new roles of management (Bleicher 1997), the management of human resources in virtual organizations (Vogt-Baatiche 1998, Hilb 1997), or the relationship between telework and virtual modes of organizing (Jackson/Wielen 1996).

If we confine ourselves to empirical studies on the genesis, structure and function of common interpretative spaces, another, very rich field of research is presented by ethnographic studies within interpretative sociology. For ethnography the analytical focus is always centered on the ways and means how local cultures are creating their own reality construction, their own common interpretative spaces through interaction and the use of native terms. A very interesting, if not to say exemplary, ethnographic case is presented by Brügger, who conducted a qualitative empirical study on the institutionalized interaction patterns of foreign exchange brokers. In the figure below an example of an actually happened, complete deal is presented. Broker Patrick sells 10 million DEM to a bank in Singapore in exchange for USD. The whole conversation lasted 10 seconds and consisted of a request »10 DM«, Patrick‘s offer »73 78« and the making of the deal with the acceptance »MINE«, which had to given within a couple of seconds in order for the deal to be successfully accomplished. All other quoted information in the example was generated automatically by the computer system (Brügger 1999).

Figure 2: Example of a conversation between two foreign exchange brokers (source: Brügger 1999)

The case is a very good example of a highly standardized, virtual environment, where participants have developed a common interpretative space with shared rules, meanings and signs, which bonds together a global community of foreign exchange brokers, who themselves are often originating from different cultures and heterogeneous backgrounds and were nevertheless successfully socialized to become a native in a global, virtual network of financial intermediation. The CIS necessary to interact in this context is established during the specific training and education of foreign exchange brokers. Very strict explicit codes of conduct are installed officially, but there are also a lot of commonly shared social conventions that have to be learned by new participants. Foreign exchange brokers are thus becoming part of two communities: one is the non-virtual environment of colleagues at their workplace, the second is the completely virtual network of relationships around the globe, which forms a distinct virtual community of foreign exchange brokers.

A related field of study is the investigation of noncommercial virtual communities, where we can also find institutionalized standards of conduct – a popular term for this social phenomenon is »netiquette« – that are part of common interpretative spaces. These standards of conduct in virtual environments have to be learned – a technical term would be internalized through secondary socialization (Berger/Luckmann 1966) – by community members and social sanctions apply in cases of non-adherence just like in non-virtual social settings. At exactly this result arrives an empirical study of codes of conduct in Usenet discussion groups (McLaughlin et al. 1995), which could be seen as the early forms of virtual communities in computer networks. On Usenet people with shared interests define their identity and roles through repeated interaction by posting messages addressed to everyone or specific prior messages. Over a certain amount of time roles and identities become socially articulated and specific patterns of interaction evolve. There are many empirical examples of the presence and development of moral community features and rich »socioemotional content« – like friendship, love, solidarity and trust (Rice/Love 1987) – in such virtual discussion groups (Rheingold 1993; 1995). Paccagnella, for example, presents a case study of an Italian discussion group on "cyber_punk" (Paccagnella 1998), Baym focuses on the "r.a.t.s." Usenet discussion group (Baym 1995), while Aycock and Buchignani introduce an ethnographic discourse analysis of communication in Usenet discussion groups on a real-life murder, which happened at a Canadian campus (Aycock/Buchignani 1995). Another very interesting phenomenon is the case of "fan-cultures", who by virtue of their object of worship already share a confined CIS and are often choosing virtual platforms as a means to uphold and institutionalize their specific CIS with likely-minded people all over the world. Barth and vom Lehm have investigated such a virtual community around the science fiction series of Star Trek and came to the conclusion that the members managed to build a complex, social space with a fully established CIS around the topic of Star Trek and showed stunning creativity and virtuosity in doing so (Bart/Lehn 1996).

Even better research fields to study the social construction of common interpretative spaces are MUD/MOO environments. While discussion groups are media platforms for asynchronous, interactive discussion of topics, which are mostly derived from non-virtual contexts, MUDs create their own contexts and establish a social space in virtual networks, where we can speak of a creation of own, distinct worlds in Cyberspace (Reid 1995, Harasim 1993). MUDs allow their participants to redefine their identity and social role in much more radical terms – Turkle and Bruckman speak accordingly of a »construction and reconstruction of self« in »identity workshops« (Turkle 1994; 1995, Bruckman 1992; 1993) – and the common interpretative space of such a virtual community has to be created in a completely virtual environment. Empirical studies of such MUD-based virtual communities reveal a high complexity of social relations with very high levels of socioemotional components (Rosenberg 1992, Turkle 1995; 1996). Aoki studied accordingly virtual communities in Japan and noted that even if most virtual social spaces started with a dominant, culturally articulated CIS, a transformation of the common interpretative space can be observed over time and a hybrid, new culture emerges (Aiko 1994). In general the whole MUD-related empirical research field is consenting to the fact that we can hardly find evidence of poorly established and functioning CIS within MUDs, and this important result in the context of virtual communities has, as noted above, implications for the discussion of virtual organizations and whether or not CIS can be established with little or no face time at all.

One methodological caveat remains in the study of virtual modes of communication, which is unfortunately extending over many scientific approaches to the topic. Studies in this area seem often to carry a connotation of authenticity, which is constructed based on the fact that all communication messages can be logged and thus – by virtue of its reduced channel capacity – no signs seem to remain unnoticed to the eye of the observer. If, however, we remember the interactional model from the first chapter, this authenticity is apparently a dangerous illusion, as we still have no information at all on the interpretative process, which is happening parallel to observable interaction patterns. Jones phrased the same argument a little differently: »Although we can ‚freeze‘ electronic discourse by capturing text and information it may contain, how do we ascertain the interpretative moment in electronic discourse, particularly as it engages both reading and writing?« (Jones 1995). This reservation shall not devalue the research results discussed above, but we have to be aware of these interpretational processes, which happen outside of any virtual environment, while drawing conclusions from research on virtual modes of interaction and community. Last but not least, we should also not forget that virtual environments are by no means simple, innocuous playgrounds for new forms of interaction, but carry certain inherent dangers, which we can poorly identify at the current state of research (Diemers 1997). We should, thus, continue research on the deeper social and psychological effects of the use of new media and communication technologies and maybe also investigate the importance of social networks for successful diffusion of new communication technologies (Schenk et al. 1997, Rogers 1979). At Carnegie Mellon a large study was conducted on the effects of intensive internet use for social, face-to-face involvement and psychological well-being. The results are quite deterrent: greater use of the internet was associated with declines in participants‘ communication with family members in the household, declines in the size of their social circle, and increases in their depression and loneliness (Kraut et al. 1998). While the first two findings are not all too alarming, if we assume that face-to-face communication is substituted with virtual forms of communication and social circles are compensatorily expanded over virtual communities and worlds, but the last finding on psychological well-being of the participants in the study calls for further research in that direction.

Final Conclusions

This paper focused on common interpretative spaces and developed a spatial model of interaction in virtual and non-virtual environments. This model comprises a geographic space, a phenomenological space, a cognitive space, a space of social representations and a common interpretative space. The CIS is outlined as a specific set of signs, shared meanings, norms and values, which are constituted through repeated interaction in social situations. In a second step, we have outlined the importance of CIS for virtual organizations and virtual communities. As organizational structures become increasingly virtualized, the questions of membership, trust, mutuality and reciprocal loyalty are paramount. One approach is to transform virtual organizations gradually into on-line communities, where membership and initiative are rewarded with status and identity (Handy 1995). Sound common interpretative spaces are, thus, the foundations on which such a transformation can be achieved.

This leads to the general question of whether patterns of repeated interaction have to take place in a shared phenomenological space, i.e. with forms of directly experienced, face-to-face communication, or to what extent the building of common interpretative spaces can be achieved with mediated forms of communication, e.g. with new media and communication technologies. To answer that question and support the argument of CIS as necessary requirements for interaction in virtual environments, different strands of empirical research have been presented, but no conclusive, final answer can be identified at the current state of research. On one hand there is evidence – especially from empirical studies in the field of virtual organizations – that virtual modes of organizing need enough face time to be successful. From the »experimental social labs« found in MUDs and other forms of virtual communities we know, however, that social patterns of interaction can be successful with zero face time and the establishment of CIS is possible under circumstances of completely virtual environments. Thus, and here I take the opportunity to formulate a daring hypothesis, if we take into account the possibilities of transforming virtual organizations into forms of virtual communities, the actual recesses and critical stances could be nothing more than a temporary phenomenon occurring during a certain transition stage, while the coming workforce generations will have no problems at all to establish fully working common interpretative spaces in virtual social spaces.

References

Aiko, Kumiko: Virtual Communities in Japan, paper presented at the Pacific Telecommunications Council Conference, 1994 (online) [ftp://sunsite.unc.edu/pub/academic/communications/papers/virtual-communities-in-japan]

Aycock, A. / Buchignani, N.: The E-Mail Murders. Reflections on "dead" Letters. In: Jones, Steven G. (ed.): CyberSociety. Computer-Mediated Communication and Community, Thousand Oaks CA: Sage, pp. 184-231, 1995

Barth, D. / Lehn, D. vom: Trekkies im Cyberspace. Über Kommunikation in einem Mailboxnetz. In: Knoblauch, Hubert (ed.): Kommunikative Lebenswelten. Zur Ethnographie einer geschwätzigen Gesellschaft, Konstanz: UVK, 1996

Baym, N.K.: The Emergence of Community in Computer-Mediated Communication. In: Jones, Steven G. (ed.): CyberSociety. Computer-Mediated Communication and Community, Thousand Oaks CA: Sage, pp. 138-163, 1995

Berger, P.L. / Luckmann, T.: The Social Construction of Reality, New York: Doubleday, 1966

Bleicher, K.: Managementpotentiale als kritische Ressource virtueller Organisationen. In: Klimecki, R. / Remer, A. (eds.): Personal als Strategie, Luchterhand, pp. 435-457, 1997

Boisot, M.H.: Information Space. A framework for learning in organizations, institutions and culture, London: Routledge, 1995

Brill, A. /Vries, M. de: Die Virtuelle Konferenz. Ein Testfall für die Qualitäten der Kommunikation im Internet, 1997 (online) [http://www.uni-wh.dde/de/wiwi/virtwirt/konf/virtkonf/virtkonf.pdf]

Brill, A. / Vries, M. de: ‚Die Wüste lebt!‘ – Theorie und Praxis der Virtuellen Konferenz. In: Brill, Andreas / Vries, Michael de (ed.): Virtuelle Wirtschaft. Virtuelle Unternehmen, Virtuelle Produkte, Virtuelles Geld und Virtuelle Kommunikation, Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag, pp. 339-371, 1998

Brosziewski, A.: Virtualität als Modus unternehmerischer Selbstbewertung. In: Brill, Andreas / Vries, Michael de (ed.): Virtuelle Wirtschaft. Virtuelle Unternehmen, Virtuelle Produkte, Virtuelles Geld und Virtuelle Kommunikation, Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag, pp. 87-101, 1998

Bruckman, Amy: Identity Workshop. Emergent social and psychological phenomena in text-based virtual reality, 1993 (online) [ftp://parcftp.xerox.com/pub/MOO/papers/identity-workshop.rtf]

Bruckman, Amy: Gender Swapping on the Internet, 1993 (online) [ftp://ftp.media.mit.edu/pub/asb/papers/gender-swapping.txt]

Brügger, U.: Wie handeln Devisenhändler?, Ph. D. thesis, University of St. Gallen, 1999 (in print)

Cash, D.C.: Information Technology and the Redifinition of Organizational Roles. In: Research in the Sociology of Organizations, vol. 9, pp. 21-48, 1991

Charam, R.: How Networks Reshape Organizations – For Results. In: Harvard Business Review, Sep/Oct, pp. 104-116, 1991

Coutu, D.L.: Trust in Virtual Teams. In: Harvard Business Review, May-June, pp. 20-21, 1998

Dachler, H.P.: Dealing with multiple views of science in research on organizing. Paper presented at the Warwick University Business School Conference on ‚Modes of Organizing: Power/Knowledge Shifts‘, April, 1997

Davidow, W.H. / Malone, M. S.: The Virtual Corporation. Structuring and Revitalizing the Corporation for the 21st Century, New York: Burlinggame Books, 1992

Davis, B.H. / Brewer, J.P.: Electronic Discourse. Linguistic individuals in virtual space, Albany NY: State University Press, 1997

Diemers, D.: Die Virtuelle Triade. Mensch, Gesellschaft und Virtualität, master thesis, University of St. Gallen, 1997

Diemers, D.: The Virtual Triad. Society and Man under the Sign of Virtuality, Essay for the 9th Honeywell Futurist Competition Europe, Munich, 1998a

Diemers, D.: Perspektiven virtueller Organisationsformen, working paper, SfS University of St. Gallen, 1998b (unpubl.)

Diemers, D.: On the Social Dimension of Information Quality and Knowledge, working paper, mcm/SfS University of St. Gallen, 1999 (unpubl.)

Drucker, P.F.: The Coming of the New Organization. In: Harvard Business Review (ed.): Harvard Business Review on Knowledge Management, Boston: Harvard Press, pp. 1-19, 1998

Friedberg, E.: Zur Politologie von Organisationen. In: Küpper, W. / Ortmann, G. (eds.): Mikropolitik. Rationalität, Macht und Spiele in Organisationen, Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag, 2nd edition, 1992

Goffman, E.: The presentation of self in everyday life, New York: Bantam, 1959

Goffman, E: Behavior in Public Places. Notes on the Social Organization of Gatherings, New York: Free Press, 4th ed., 1969

Hall, S.: The Work of Representation. In: Hall, Stuart (ed.): Representation. Cultural representations and signifying practices, London: Sage, pp. 13-74, 1997

Handy, C.: Trust and the Virtual Organization. In: Harvard Business Review, May-June, pp. 40-50, 1995

Handy, S.L. / Mokhtarian, Patricia L.: The Future of Telecommuting. In: Futures, vol. 28, nr. 3, pp. 227-240, 1996

Harasim, L.M.: Networlds. Networks as social space. In: Harasim, L.M. (ed.): Global Networks. Computers and international Communication, Cambridge MA: MIT Press, pp. 15-34, 1993

Hilb, M.: Management der Human-Ressourcen in virtuellen Organisationen. In: Müller-Stewens, Günter (ed.): Virtualisierung von Organisationen, Stuttgart: Schäfer-Poeschel, pp. 83-94, 1997

Jackson, P.J. / Wielen, J.M. van der (ed.): London ’96. New international perspectives on telework. proceedings of the workshop from Telecommuting to the Virtual Organisation, Tilburg: Work and Organisation Research Centre, 1996

James, W.: Principles of Psychology, New York: Henry, volume I and II, 1890

Jones, S.G.: Understanding Community in the Information Age. In: Jones, Steven G. (ed.): CyberSociety. Computer-Mediated Communication and Community, Thousand Oaks CA: Sage, pp. 10-35, 1995

Kiesler, S. / Siegel, J. / McGuire, T.W.: Social Psychological Aspects of Computer-Mediated Communication. In: American Psychologist, vol. 39, nr. 10, pp. 1123-1134, 1984

Komito, L.: The Net as a Foraging Society. Flexible Communities. In: The Information Society, vol. 14, pp. 97-106, 1998

Kraut, R. / Patterson, M. / Lundmark, V. / Kiesler, S. / Mukopadhyay, T. / Scherlis, W.: Internet Paradox. A Social Technology That Reduces Social Involvement and Psychological Well-Being? In: American Psychologist, vol. 53, nr. 9, pp. 1017-1031, 1998

Luckmann, T.: Von der unmittelbaren zur mittelbaren Kommunikation (strukturelle Bedingungen). In: Borbé, Tasso (ed.): Mikroelektronik. Die Folgen für die zwischenmenschliche Kommunikation, Berlin: Colloquium Verlag, 1984

March, J.G. / Simon, H.A.: Organizations, New York, 1958

Markus, L.M. / Bikson, T.K. / El-Shinnawy, M. / Soe, L. L.: Fragments of Your Communication. Email, Vmail, and Fax. In: The Information Society, vol. 8, pp. 207-226, 1992

McLaughlin, M.L. / Osborne, K.K. / Smith, C.B.: Standards of Conduct on Usenet. In: Jones, Steven G. (ed.): CyberSociety. Computer-Mediated Communication and Community, Thousand Oaks CA: Sage, pp. 90-111, 1995

Mettler-Meibom, B.: Wie kommt es zur Zerstörung zwischenmenschlicher Kommunikation? In: Rammert, Werner (ed.): Computerwelten-Alltagswelten. Wie verändert der Computer die Wirklichkeit? Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag, 1990

Morgan, G.: Toward a more reflective social science. In: Morgan, G. (ed.) Beyond Method. London: Sage, pp. 368-376, 1983

Morgan, G.: Images of Organization, Beverly Hills, 1986

Morgan, G.: Paradigm diversity in organizational research. In. Hassard, J. and Pym, D. (eds.) The theory and philospohy of organizations. London: Routledge, pp. 13-29, 1990

Mosco, V.: Myth-ing Links. Power and Community on the Information Highway. In: The Information Society, vol. 14, nr. 1, pp. 57-62, 1998

Nohria, N. / Berkley, J.D.: The Virtual Organization. Bureaucrazy, Technology, and the Implosion of Control. In: von Heckscher, Ch. und Donellon, A.: The Post-Bureaucratic Organization. New Perspectives on Organizational Change, Thousand Oaks: Sage, pp. 108-128, 1994

Nonaka, I. / Konno, N.: The Concept of ‚ba‘. Building a Foundation for Knowledge Creation. In: California Management Review, vol. 40, nr. 3, pp. 40-54, 1998

Paccagnella, L.: Language, Network Centrality, and Response to Crisis in On-Line Life. A Case Study on the Italian cyber_punk Computer Conference. In: The Information Society, vol. 14, nr. 1, pp. 117-135, 1998

Powell, W.W./ Koput, K.W./ Smith-Doerr, L.: Interorganizational Collaboration and the Locus of Innovation. Networks of Learning in Biotechnology. In: Administrative Science Quarterly, vol. 41, pp. 116-145, 1996

Pugh, D.S. / Hickson, D.J. (eds.): Organizational Structure and its Context. The Aston Programm I, Westmead, 1976

Reid, E.: Virtual Worlds. Culture and Imagination. In: Jones, Steven G. (ed.): CyberSociety. Computer-Mediated Communication and Community, Thousand Oaks CA: Sage, pp. 164-183, 1995

Rheingold, H.: A slice of life in my virtual community. In: Harasim, L.M. (ed.): Global Networks. Computers and international Communication, Cambridge MA: MIT Press, pp. 57-80, 1993

Rheingold, H.: The Virtual Community. Finding Connection in a Computerized World, London: Minerva, 1995

Rice, R.E. / Love, G.: Electronic Emotion. Socioemotional Content in a Computer-Mediated Communication Network. In: Communication Research, vol. 14, pp. 85-108, 1987

Rogers, E.M.: Network Analysis of the Diffusion of Innovations. In: Holland, Paul / Leinhardt, Samuel (eds.): Perspectives on Social Network Research, New York: Academic Press, pp. 137-164, 1979

Rosenberg, M.S.: Virtual Reality. Reflections of Life, Dreams, and Technology. An Ethnography of a Computer Society, 1992 (online) [ftp://parcftp.xerox.com/pub/MOO/papers/ethnography.txt]

Schenk, M. / Dahm, H. / Šonje, D.: Die Bedeutung sozialer Netzwerke bei der Diffusion neuer Kommunikationstechniken. In: Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie, vol. 49, nr. 1, pp. 35-52, 1997

Schütz, A. / Luckmann, T.: The Structures of the Life-World, vol. 1, London: Heinemann, 1974

Schütz, A. / Luckmann, T.: The Structures of the Life-World, vol. 2, London: Heinemann, 1983

Stegbauer, C.: Die virtuelle Organisation und die Realität elektronischer Kommunikation. In: Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie, vol. 47, nr. 3, pp. 535-549, 1995

Stegbauer, C.: Management by E-Mail. Die Nutzung von elektronischer Kommunikation in der Praxis. In: GDI-Impuls, nr. 1, pp. 46-53, 1996

Tönnies, F.: Community and Society, New York: Harper and Row, 1963

Turkle, S.: Constructions and Reconstructions of Self in Virtual Reality. Playing in the MUDs. In: Mind, Culture and Activity, Issue 3, vol. 1, pp. 158-167, 1994

Turkle, S.: Life on the Screen: identity in the age of the Internet, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995

Turkle, S.: Virtuality and its discontents. Searching for community in cyberspace. In: The American Prospect, vol. 24, winter, pp. 50-57, 1996

Uzzi, B. / Davis-Blake, A.: Determinants of employment externalization. A study of temporary workers and independent contractors. In: Adminstrative Science Quarterly, vol. 38, pp. 195-223, 1993

Vogt-Baatiche, G.: Das virtuelle Unternehmen. Anforderungen an die Human Resources, Ph.D. thesis, Universität St. Gallen, 1998

Voss, W.: Telearbeit. Erfahrungen, Praktischer Einsatz, Entwicklungen, München: Hanser, 1998

Weick, K.E.: Cosmos vs. Chaos. Sense and Nonsense in Electronic Contexts. In: Pugh, Derek S. (ed.): Organization Theory. Selected Readings, New York: Penguin, 1996

any meaningful commentary or critique regarding statements made in this article are very welcome:

lic. oec. Daniel Diemers CEMS

for contact call +41 71 224 28 17 or e-mail to daniel.diemers@unisg.ch

affiliations of the author: University of St. Gallen (HSG) in Switzerland, Sociological Seminar (SfS-HSG), Institute for Media and Communication Management (mcm-HSG), Swiss Association for Sociology (SGS), Swiss Research Committee for Interpretative Sociology, Swiss Association for Future Research (SFZ).